"There seem to be two categories of musicians, those who have side jobs and those who lie."

The trials and tribulations of being a musician in post-Covid Italy

The image of an artist is a complex one. On one hand there is the glitz and glamour of the globetrotting touring artist with an aspirational lifestyle and social media presence to boot, and on the other, the moonlighting creative who is struggling to pay their rent. And then an increasingly diminishing group of those who fall somewhere in-between. Alessandro Pilo investigates the situation in Italy where he speaks to several figures from the local music scene who grapple with the disastrous effects of the Covid pandemic on the live music industry.

Soviet Soviet

As 2019 came to a close, the Italian post-punk trio Soviet Soviet was ready to celebrate an important milestone in their career. Formed in 2008, the band, renowned for their electrifying live performances, had extensively toured Europe and South America, with a mishap in the U.S. along the way. Their dark, atmospheric sound was set to reach China through an upcoming 2020 tour spanning through the country, including a show in the city of Wuhan. As you may have guessed, the tour never happened. "We were clued in more than anyone else in Italy about what was happening there, and we sensed what was about to come," Alessandro Ferri, the drummer of Soviet Soviet, tells me over the phone.

"If we had come from a more privileged background, perhaps we could have weathered the pandemic differently."

Soviet Soviet’s path has been pretty wild for an Italian band, particularly one hailing from Pesaro, a small city in central Italy. From the very start they’ve been hitting stages more internationally than at home. "Sometimes fans at our Italian gigs hit up our merch stand, chatting us up in English, only to be floored when they find out Soviet Soviet is actually an Italian act." Their cash flow was unstable. One month, they’d rock a European tour; then, for the next couple of months, silence. Despite the unpredictability, they managed to sketch out plans and have an idea of their financial prospects. That’s why for Ferri and the bass player Andrea Giometti - by that time the guitarist Alessandro Costantini had left the band and was replaced by touring members - gigs and merch sales had become their sole income stream. "Our lifestyle was stripped down, devoid of extravagance, but with some sacrifices we could make ends meet."

With tours canceled and facing the loss of their income for the time being, Giometti and Ferri made a pivotal decision: they both sought full-time employment. Additionally, Ferri embarked on a new chapter by starting a family with his partner. Now, he toils from 9 to 5 in a warehouse, while Andrea has taken up a blue-collar position at a factory, occasionally working night shifts. Now balancing their family responsibilities and full-time jobs, they struggle to coordinate their performances around holidays and work schedules. The once-frequent long tours have become increasingly challenging to organize. On a positive note, Ferri has found unwavering support from his partner, "after all, we first met at a Soviet Soviet show, and she has remained a dedicated fan ever since. That’s why she doesn’t mind that most of my annual leave is devoted to touring."

Ferri acknowledges that a minimalist lifestyle as a drummer was more enjoyable than moving boxes all day. Nevertheless, he approaches this new situation with a Zen-like mindset. "If we had come from a more privileged background, perhaps we could have weathered the pandemic differently. Maybe Soviet Soviet could have finally released a new album, and the band might have taken a different trajectory, for the better. But life unfolded in unexpected ways, and now music is just one of the elements around which our lives orbit—alongside work and family."

In a twist reminiscent of a classic meme, at the moment there exists a curious divide between the band's real-life experiences and how others perceive them. They are still kicking it with European gigs and a recent mini tour in South America, they have racked up more than 33 millions streams on Spotify, and they are holding steady with 120,000 monthly listeners. From an outsider's view, they’ve nailed it. "In reality, from Spotify we roughly earn a few hundreds euros every six months, with half claimed by our American label Felte, as per the agreement. In the meanwhile I speak to you from the warehouse during my lunch break, and later Andrea is heading to his night shift at the factory.” Ferri is not surprised by these misconceptions, when he started playing more professionally, he also thought that once he earned a decent fee, it meant he had made it. "I forgot to consider that the money needed to be split—the sound guy needed his cut, and we had to cover gas and van fixes. In the end, not so much ends up in your pocket. And with tour expenses going up, the situation isn’t exactly improving."

Italy was the world's first country to place its entire territory under lockdown. For artists and music workers that meant a sudden stop to their income. While certain temporary financial support measures were put in place, a significant number of individuals were left out due to not meeting specific economic criteria. Additionally, many others lacked access to temporary support forms because they operated within the realms of undeclared work and the informal economy—a prevalent situation in the Italian music sector. Marco Trulli is a cultural worker and a national executive member of ARCI, the largest Italian non-profit association focused on culture, social issues and democratic participation, to which around 5,600 clubs across Italy are affiliated. He tells me over email that since the pandemic aftermath, ARCI, along with other trade associations and live entertainment industry groups, have been advocating for stable measures to support entertainment workers. They also aim to introduce basic universal income programs to compensate for musicians’ intermittent work. This initiative would align Italy more closely with countries like Germany, France, or Belgium, where artists have the opportunity to seek state funding or receive a monthly stipend after playing a certain number of shows. However, instead of addressing the problem structurally, the Italian government opted for yet another short-term patch, a one-off payment—an average of 1,500 euros—meant to ease artists’ struggles. Worse yet, beneficiaries plummeted from 300,000 to 20,000. Italy’s general neglect of cultural workers should not be surprising. Despite presenting itself as a creative heavyweight, Italy falls short in investing in new artistic production. The country ranks third from the bottom in the EU when it comes to state spending on the cultural sector, allocating only around 0.5% of its GDP, while the European average stands at 1%.

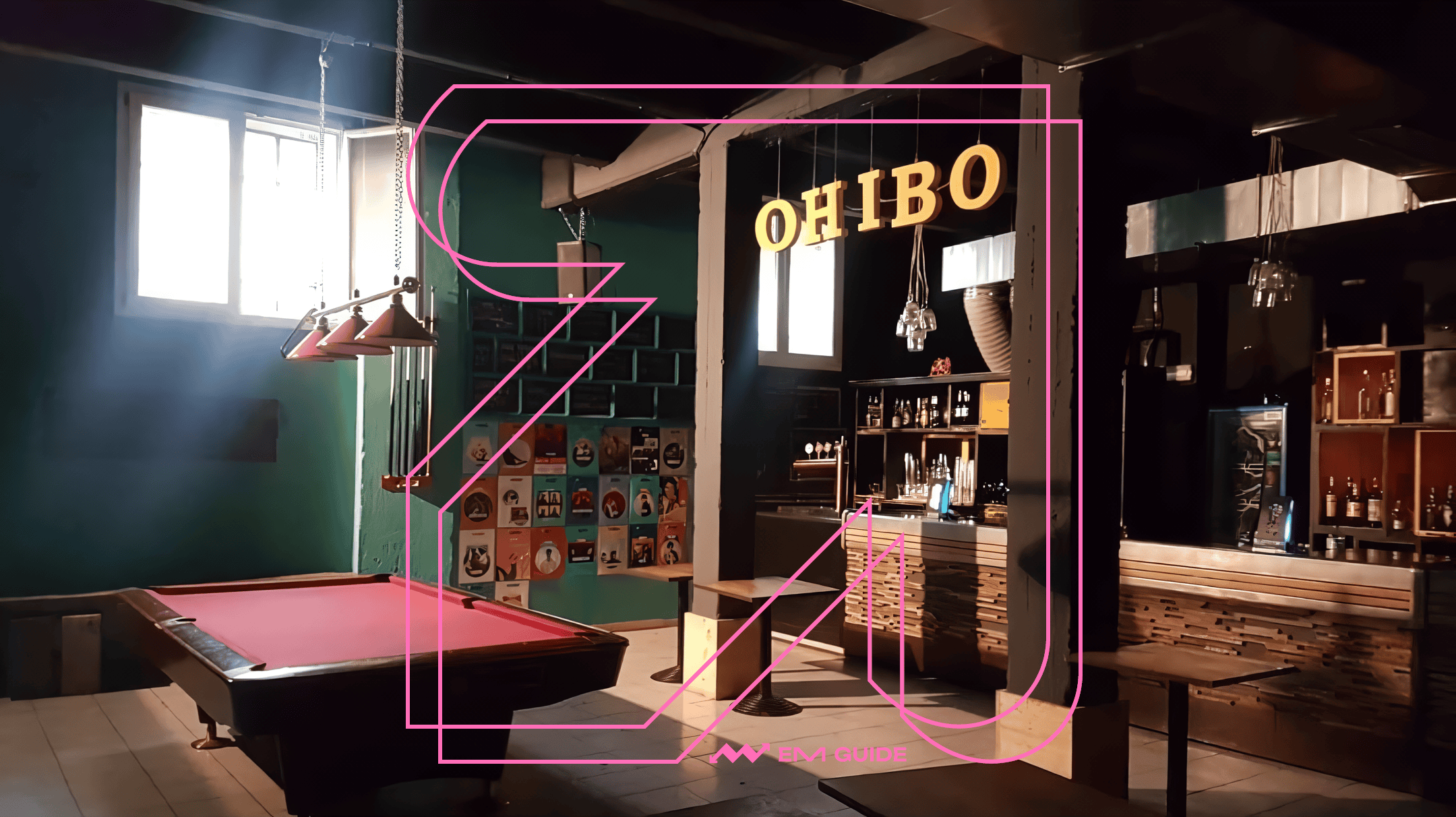

Simone Castello (Ohibò)

"We became a small success story in Italy, a country where the saying ‘con la cultura non si mangia’—culture doesn’t put food on the table”—is all too common."

Ohibò was an ARCI affiliated cultural hub and music club in downtown Milan. Simone Castello had been at the helm since 2017 as the artistic director. He joined Ohibò when the financial situation was bleak, but by the end of 2019 the association’s account was active, and the outlook was brighter. “We became a small success story in Italy, a country where the saying ‘con la cultura non si mangia’—culture doesn’t put food on the table—is all too common. Our cultural enterprise defied the odds, demonstrating that it could operate with professional efficiency, akin to a small enterprise, while remaining financially sustainable”. Amid the chaotic early months of the pandemic, as rental costs remained unchanged and the bills were piling up, Ohibò decided to terminate the leasing contract and halt activities at the beginning of June 2020. The impact resonated throughout Milan and the entire country due to a Facebook post announcing the closure, which reached nearly 2 million users organically. "Due to my position, I wasn’t included in the decision-making process. Yet, I wonder if the association could have tried harder. Perhaps launching a crowdfunding campaign,— even if it meant raising funds for an unused space—could have been an option. However, the uncertainty about the future led to playing safe." As Covid unfolded, Serraglio, another historic venue in Milan, met a similar fate.

Before the pandemic swept across Italy, the country already held the dubious distinction of being the only EU member where average wages had declined over the past three decades. But soaring inflation is now squeezing the wallets of young Italians even tighter, forcing them to carefully weigh their concert choices. According to Castello, an indie music label owner and concert organizer, underground programs in small-to-mid-sized alternative venues are the ones getting the short end of the stick. “The trauma that has affected younger generations during the Covid pandemic has definitely played a role in this. A specific age group had to alter their habits and relinquish their carefree lifestyles. As a consequence, certain categories of people who were previously more culturally active are now attempting to reclaim lost time and dedicate it to disengaged leisure." Castello looks at the post-pandemic landscape with a heavy heart: some alternative clubs, once focused purely on underground programs, need to adapt and have to navigate a delicate balance between more complex offerings and mainstream events increasingly oriented toward diversion. “Even hosting an exceptionally cool band may only fill half the venue, while DJ sets featuring Italian music or karaoke nights consistently sell out."

The bigger impact of this trend is visible: "Before Covid, certain bands or performers effortlessly organized thirty-date tours across the country. Now, even those with similar followings and press recognition struggle to secure more than five gigs." According to Castello the absence of live music opportunities in the short term erodes a musician’s primary income stream. "But over the long term, it has a profound demoralizing impact, leaving many talented performers questioning whether investing more time, energy, and money is worthwhile without any prospects for the future." Castello takes pride in Ohibò’s role in propelling Italian performers such as Calcutta and the band Pinguini Tattici Nucleari, who were some of the most prominent indie musicians at the time and are now filling larger venues. Yet, these success stories were built organically on the groundwork of hundreds of concerts, something that in his opinion could not be possible today. "Before the pandemic, the battle for attention was intense, but there existed a healthier amount of available opportunities—whether in the form of venues, media exposure, or public. Even performers who preferred slower, step-by-step careers found it easier to emerge." As alternative venues shutter, music magazines cease operation, and the public dwindles, the only environment that remains will favor musicians who can rapidly generate hype and economic success. The Italian post-Covid landscape increasingly resembles a capitalist-driven monoculture, warns Castello.

Castello frequently engages in candid conversations with international musicians. They seem to be part of a system that embraces a more professional and healthier entrepreneurial approach, unlike Italy. But even overseas, things aren’t all sunshine and rainbows. A fresh UK census reveals that nearly half of working British musicians earn less than £14,000 a year. Meanwhile, a recent article that appeared on The Guardian paints a stark reality for UK bands, grappling with the Catch-22 of launching new tours, fully aware that due to soaring touring costs they’ll emerge from the experience drowning in debt.

Amidst the general neglect from the Italian governments, glimmers of hope emerge through cultural support legislation championed by specific local authorities. In Emilia Romagna, a regional law provides tailored contributions to live music venues, while in the southern region of Apulia, the initiative Puglia Sounds supports local artists and musicians through public funding calls. These funds cover every stage, from creative production to album releases, and even facilitate tours within Italy or abroad. A recent standout is Vipra, a young pop punk artist originally from Apulia who embarked on a Japanese tour, an otherwise unthinkable feat for an emerging indie performer singing in Italian. But for Southern Italian musicians the ultimate career move still involves packing their bags and heading to other Italian cities with a more vibrant cultural and musical scene.

Maru Barucco

Maru Barucco, a 31-year-old musician from Sicily, relocated up north, in their case to Bologna. There they enrolled in an electronic music curriculum at Conservatorio Martini di Bologna, which not only expanded their musical horizons but also opened doors to job opportunities related to experimental music. These opportunities ranged from sound installations to audiovisual compositions, including live electronic music performances and artistic residencies. Despite these prospects, earning a living only from their profession remains challenging for Barucco, who jokes: "In my community, there seem to be two categories of musicians, those who have side jobs and those who lie."

“Even in a stable job you’re expendable, so once you take the risk, you might as well do it for the job you love.”

Over the years, Barucco has taken on a variety of roles: baker, shopkeeper, waiter, assistant cook, and most recently, shelf-stacker at the local Ikea store. However, these side jobs have come at a cost. Missed grant deadlines due to lack of time, endless social and networking opportunities slipping away, and even showing up unprepared for paid project rehearsals—all of these experiences created a significant divide between Barucco and those with more affluent backgrounds. Nevertheless, a year ago, Barucco’s efforts paid off when they received an invitation to play synths, bass, and electronics in Daniela Pes’ live performances, the latest sensation in Italy’s underground scene for her exoteric art-electronic sound. Initially, the team leader at Ikea was understanding, allowing flexible shifts. But as attention around Daniela Pes grew, balancing a side gig with a growing tour schedule became tougher for Barucco. When yet another request for time off was denied, they decided it was time to take the leap and pursue music full-time. For some people, it could be life's crossroads: accept risk and sacrifice economic security, or prioritize stability. However, for Barucco, the decision was self-evident. "Even in a stable job you’re expendable, so once you take the risk, you might as well do it for the job you love."

While they have consistently worked hard to be independent, Barucco acknowledges a certain degree of privilege. "A few years ago, my family stepped in to help me purchase a flat in Bologna. Given the escalating rents due to gentrification—where even run-down rooms can cost 600 euros per month—if it hadn’t been for my family, music would probably have slid back into being just a hobby, confined to a rehearsal room once a week." Barucco’s situation remains unstable: during months when they are extensively on tour, they can earn around 1,400 euros monthly. However, there are leaner months when they barely manage 400 euros. Barucco has begun envisioning a future where music is their sole occupation. It’s the lifelong dream, yet this prospect also stirs anxiety; until now, a side gig helped them protect creative freedom. But as economic stability now depends fully on the musical career, Barucco hopes to navigate it without compromising artistic integrity.

Alessandro Pilo is an Italian freelance journalist based in Budapest. He has written for Vice, Wired, HuffPost, and La Stampa, among others, covering politics, environmental issues, and underground culture.

The original cover image is the courtesy of Ohibó.

This article is an EM GUIDE special curated by the editors of the EM GUIDE members and created in response to current trends and issues of the regional and global music industry.