Would you like some help writing that? Why the revolution won’t be AI-generated

Barely two years into the generative-AI era, what kind of revolutions or nightmares are coming true? Are we truly more productive? What are its impacts in the cultural and artistic worlds? And will there be room left for us?

A text by Alexander Mayor

It began rather like a magic trick. A text entry field at the top of an unadorned web page, ChatGPT transformed the academic sounding discipline of artificial intelligence, into a public novelty overnight. Ask it anything and kazaaam! A thoughtful, cheery, response in seconds. Whoa.

Finally, your computer had become someone you could talk to, demand things of, and make unlikely requests of. GPT2 had been profiled by John Seabrook back in 2019, and even then the technology looked intriguing and powerful. But nothing prepared you for the actual experience of using it. As someone old enough to remember the 1980s home computer era, when you had to type in the actual program code before the machine would do anything but blink a cursor at you, well, we appeared to finally be living in the future.

Time passes… A few mad AI-related services (and some truly terrible products, looking at you Humane AI pin) launch. Simply everyone adjacent to the tech sector has crowbarred the letters ‘AI’ into their product descriptions and the annual report to shareholders. A new black gold is gushing. More time passes. A presidential candidate uses cheap AI image generation to suggest Taylor Swift is surprisingly on board.

Facial and vocal trickery that was once only possible in the Mission Impossible films is now being used by fraudsters to rob companies of millions. Tech bro podcasters like Lex Fridmann have been gleefully predicting either imminent societal breakdown as all employment ‘goes away’, or the arrival of better-than-human artificial general intelligence (AGI), at which point our enslavement is presumably the main outcome.

What really is happening in the real world? As someone who produces music and also writes for a living, I should be feeling panicked right? The robots are at the gates! In reality, although this is incredibly potent technology, it’s already clear that the some of the hype is deranged and also that AI, like every product before it, has to live in a human world, shaped by our actual needs, behaviours and realities. So, no grand universal theories here, but a few observations about how generative AI seems to be unfolding in our thankfully still-all-too-human world.

Delighted to be deleted?

For decades we have been labouring under the impression that we were building a knowledge economy. Physical labour would shrink, and value would be produced by ever more sophisticated combinations of professional expertise: designers, engineers, scientists, artists, linguists, chemists, all collaborating on things we need (before handing them over to machines to build).

From this settled picture, generative AI is a rude awakening. Both large language models (LLM) like ChatGPT, Llama and Gemini, and older ‘machine learning’ approaches, essentially get their hands around large parts of this sort of labour, using prediction and parameterisation to brute force productive outcomes of different sorts from vast quantities of data. By turning human thought and creativity into a statistical, probabilistic and mathematical processing task, and drawing on the incredible power of arrays of chips from NVIDIA and others, Silicon Valley has gifted us a way to potentially evade much of this ‘knowledge’ labour and need for individual human experience.

As this kind of generated output increases, our individual, personal input and authenticity becomes diluted. This presents a problem given we’ve developed a culture where “I” is the basic unit of currency. ‘Me! I made this!’ In a knowledge economy, it’s the ‘I know and I can do’, that you’re buying. If I’m just a dumb button pusher, (sorry, ‘prompt engineer’) why does the company need me at all? For many tasks, the AI generated outcome will be good enough, so thanks for sending in your CV and all, but we’re on a bit of a hiring freeze… Hence the fear of mass unemployment, particularly for industries where work comprises programmatic or repeated tasks, like customer service or administration.

Meanwhile, there has been an unseemly haste on the part of the biggest tech players like Microsoft and Google to insert AI features into their all pervasive operating systems and software. You’ve probably noticed that every document or email now prods you to let the AI do the pesky writing for you. Partly this is because they want to get a return on the billions of dollars sunk into building these tools. But the speed also reveals an indication of the industry’s reliance on a build-it-and-they-will-come ethos. In truth, no one knows if generative AI actually is really some great productivity unlock or not.

Anecdotal evidence shows that a huge number of people initially enthused about ChatGPT only used it a couple of times before largely forgetting about it. Cringe-making use case demos from the likes of Google (unable to help your daughter write fan mail to their Olympic hero? Get a machine to write it!) have hardly helped make the case that this is something that fits into daily life.

Uncomfortable generators

The core of the tension lies perhaps in the ‘g’ of ChatGPT’s meaning: it’s a generative pre-trained transformer – it’s been trained on a huge corpus of data, and can transform it from one form to another, generating new things. Traditionally, when we work, whether as designers, writers, scientists or anything else, we are talking about the process of thinking, considering, imagining, discussing, and then only later ‘production’. We haven’t typically used the word ‘generate’ to describe this process, precisely because its mechanistic implications weren’t really a good fit. Things people don’t say: “my wife and I have been enjoying that album you generated – it was playing in our robotaxi home the other night!”

There are two issues here. One is what we see printed on the inside flap of a novel, “Michael Author has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work…” We are declaring “I did this” which isn’t the same as “I was the person who generated this.” It’s a declaration of rights, but also an acknowledgement of responsibility. However opaque and mysterious our creativity is to us, when we’ve produced something it’s ours, warts and all.

Technology’s ability to beguile and make fools of us couldn’t better be summarised than the revelation in September 2023, that Amazon had had to institute a rule forbidding its Kindle authors from publishing more than three books a day on its platform. You can picture the graph with high productivity at one end… and zero quality at the other.

Of course, some will argue that this is just the usual way social convention and moral traditions are reshaped by tech. We’ll see. However, a second problem, below, is likely to compound the inauthenticity of this position.

Truthiness

The second is the problem that LLM based AI tools simply have no idea what is true, and at present lack the means to correct themselves. As Michael Townsen Hicks, James Humphries and Joe Slater, the authors of a provocative paper “ChatGPT is bullshit” state, these language models are built to be indifferent to the truth. They point out that the use of the word ‘hallucination’ for the mad and strange things that LLMs will produce is actually quite misleading. ChatGPT is ‘a bullshitter’ because like a low-rent politician on the make, it’s simply making a series of predictions based on a prompt and delivering the response to you in words or pictures. At no point can it either know what’s true or care about the outcome. (Their whole paper is well worth a read on the technology’s limitations.)

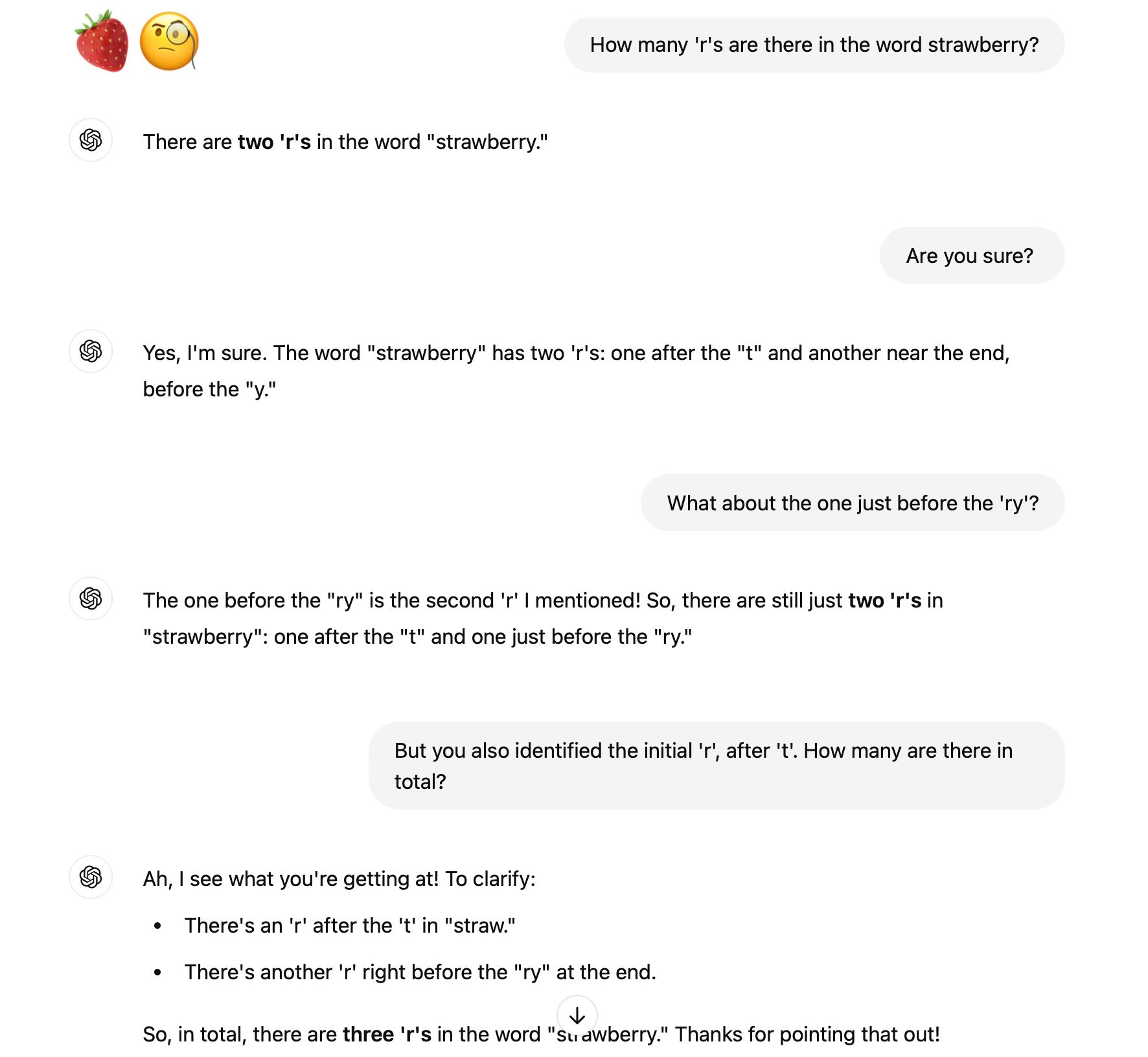

This was beautifully demonstrated recently by a woman’s hard-fought battle to persuade ChatGPT that there are in fact 3 ‘r’s in the word strawberry. The exchange is fun and instructive of where we’re at:

So for knowledge workers, the seductive new deal is this: produce vastly more ‘output’ at great speed, but having done none of the analysis, research or thinking yourself, understand that you’re now in partnership with a bullshitter. In fact, your job is fact checking the glib assertions of a software model that cost up to a billion dollars to train. Is this the role we foresaw for ourselves in the glorious information age?

With generative AI tools, we are presented with a funhouse mirror reflection of ourselves, one that can be delightful or nightmarish depending on the context and the output. That reflection is only seductive because we find ourselves terribly interesting, which is in part true because our own intelligence and thinking remain largely mysterious to us. To encounter a talking, writing, ‘thinking’ computer is at one level to think we have found ourselves – with language as the common element. (I think in words and I speak. This technology responds in words and it speaks. Therefore we are the same.) This is of course a mistake, albeit one driving insane corporate valuations for certain tech companies.

Degenerating creativity?

Why does any of this matter? Well, as humans, being respected for our labour, our effort, our achievements seems to be vital to our lives as social animals. Even if no money changes hands, what we learn, what we do and who we do it with, are fundamental to what it means to be ourselves. The philosopher John Locke had a go at trying to define the relationship between work and property, fixating on how we mix our labour with the raw materials around us with this effort, this process, somehow our natural rights to the results. Locke was writing about 80 years before the industrial revolution, and the beginning of our enduring devotion to machines, efficiency and productivity. The machines were working for us – is the danger now that we are simply the work inside the machine?

The ‘fake me’ media

The implications for the creative world are only just starting to ricochet around. A personal declaration here. Like many I’ve been playing around with generative AI image and video tools. Largely because the musical duo I’m part of are located on different continents, we used these things to generate animated versions of ourselves based on the few photographs we had to hand. Using Midjourney (images) and KaiberAI (animation) we were able to create video clips and still images that I personally could never have produced (I can scarcely draw a stick man). The results were sometimes interesting enough to share, but contrasted with the joy and effort and pride that came from writing and producing our the music itself, this process made me uneasy. Certainly plenty of other musicians and artists have been justly quick to view generated-AI as cheating, inauthentic or somehow lesser (even if it’s not always easy to articulate why.)

This uneasiness echoes in a way the pushback when synthesizers and drum machines first appeared. In 1982, the UK’s Musicians Union even started a campaign to have them banned – take that, Kraftwerk! – pointing to the likely unemployment that would follow. This concern seems almost charmingly naive now, but tensions between individual human talent and any kind of technological automation, seem to be baked into the equation again.

So there I was – someone with no visual artistic skill, suddenly in the game of producing things that I couldn’t make. Again, that problem – who wants to be seen as “a generator”?

Now I know a number of very talented visual artists, but candidly I didn’t have the PR budget to commission them to go off and create me animations for every daft social media post. So was I cheating them by using Midjourney? Or cheating myself by turning out images I hadn’t really made? Does AI make you an independent DIY punk or just a horrible sell-out? Do any of these considerations even mean anything any more?

The novelist Ted Chiang articulated this quandary well in a recent New Yorker piece when he observed that “generative A.I. appeals to people who think they can express themselves in a medium without actually working in that medium.” He’s right that these are moves we wouldn’t normally presume to make. And yet here we are, with itchy fingers, staring at the blinking prompt field, wondering what we might produce. It seems unlikely that this genie returns inside the lamp

The price of ‘fair use’

Meanwhile in Spring 2024, Suno and Udio, two AI music generator services who clearly believed songwriter and publisher copyrights were something to worry about later, got busted by the Recording Industry Association of America’s most shark-like lawyers. The issue here was the perennial one about what training data was used to make the generative AI service function. Users had discovered that with a bit of judicious prompting, they could get the software to ‘generate’ a suspiciously accurate soundalike Mariah Carey Xmas song, suggesting the platform had really just spent the weekend training itself using a Spotify premium account or something. Is that a copyright infringement? It certainly feels like it. Whether the old pre-digital world of copyright will endure in a world full of ‘generation’ remains to be seen. (Never bet against Hollywood and the music industry though.)

In these kinds of examples, AI has led us to another moral quandary. Not only might you not actually be ‘working’ or ‘creating’ when you use these tools, the output might also be a form of theft, whether from painters, graphic designers, composers or authors. All of the AI services currently using LLMs are hoping that the ingestion of the internet’s entire catalogue of pages, images, songs, and movies counts as ‘fair use’.

The courts have yet to decide on that issue. But the tech industry’s bet seems to be the usual move-fast-and-break-other-people’s-things and hope that the tools become so compelling that their land grab involved becomes some kind of done deal or new normal. Money and scale and hand waving will fix these things, somehow. When in April 2024 Joanna Stern from the Wall StreeFFt Journal interviewed OpenAI’s CTO, Mira Murati about what sources their impressive video generator, Sora, was trained on… Murati, sensing a legal tiger trap, stonewalled. (The fact that the CTO of the company didn’t think this question would come up, is a bit telling.)

In reality, OpenAI has already started paying larger publishers whose content has been scraped by ChatGPT, an acknowledgement that the legal rights haven’t entirely been swept aside in this bold new age. It’s also a presumably a land grab to ensure other models don’t have access to the latest sources of news and data in future.

Novelty vs value

Of course use cases have appeared, where these ‘generative’ outputs are proving valuable. Designers and TV/film graphics people are already using generative-AI tools to shave time off the initial visualisation phase, working up demo ideas. Writers are testing headlines in ChatGPT and testing their arguments against the service’s perky if vanilla suggestions. Agencies are generating concepts for ad campaigns or tag lines or pitches. Students are able to cheat at their essays even more efficiently, leading inevitably perhaps to a kind of arms race, with professors investing in AI detection software. For many software developers, development and coding tasks feel they have been accelerated substantially. Language and translation tools have become more powerful – hey, Billy Corgan can now promote shows in any language (admittedly cool). But in every setting there remains the risk that if you don’t know what you know, you won’t understand what the technology confidently produces on your behalf.

Two years or so into the generative AI revolution and it feels its value is impressive in pockets, but hardly a brave new world. It was telling that Apple, playing catch-up on AI in its 2024 operating system update, has taken a more cautious approach to the implementation of generative AI features in its platform and apps. Perhaps echoing a notorious meeting between Steve Jobs and the Dropbox founders over a decade ago (‘you don’t have a product, you have a feature…’ the great man is said to have caustically observed), Apple seems to have started from the question of what the user really might want to achieve. Summarising and restyling text in emails and documents, using natural language to make its voice assistant Siri more useful, generating personal emoji, erm… that’s it for now?

Putting art into the machine

The digital age has always promised to deliver one of capitalism’s core virtues – the ability to create once, and repeat many. Generative AI promises a new version of this ‘efficiency’ or ‘productivity unlock’, only this time the tools appear at first glance to have gained that most intangible of strengths, creativity.

The 2023 Hollywood writers strike was in part a push back by creatives who didn’t want their roles to be supplanted by generative AI that boshed out the body of scripts, with their role diminished in scope and value to a few lower paid rewrites at the end. They won that round, but the strong arm tactics of a big business that thinks it has identified a short cut to cheap and plentiful outputs, will likely return soon enough.

The strike was called off and a deal struck on the non-use of AI generated scripts. Yet the same year, a suspiciously young looking Harrison Ford runs around a castle in The Dial of Destiny – an impressive technical feat managed in part by AI de-ageing software that had been trained on many hours of old footage of the actor. Of course, a star of the stature of Harrison Ford has the power to control this process. But the lure for the industry would be to reuse every performance they have on film, by beloved performers who can’t push back from beyond the grave. Tyler Perry even mused about cancelling investment in a new studio facility when he saw OpenAi’s Sora demos.

The same somewhat grisly excitement at the prospect of reusing talent ad infinitum, has hit the book world. Apple Books and Amazon (Audible) have tried to reuse actors’ voices as source material for their own AI reading technologies. I’ve worked with a wonderful voiceover artist in the UK for some years, and she reports that it’s a depressing time for voice talent (and makes every new client sign a form committing not to steal her voice for training data.)

Once more, generative AI era pits one group of human ‘value extractors’ (tech firms) against an older one (studios, publishers, etc), with hardworking creative individuals again squeezed in the middle.

Slippery people

The AI innovations keep coming, insidiously blurring the human and digital worlds. Google’s latest smartphone allows you to use AI to ‘edit your memories’ - you can ‘fix’ photos by adding things that weren’t there, another win for novelty over authenticity. We’re all bad at taking photos, so now they can be what you want, not what you saw. The appeal in the moment is clear; yet years later, when you rediscover that photo, what will be you see? Something that happened, or something you generated? Were you really there at all? The implications for photography’s role in court cases will certainly be interesting to watch.

We all know generative AI isn’t going away, and will likely gain in productive promise as access to data and computing power increase. We also know that we still value our work for what it requires of us and for the connections it enables us to make, with people, ideas, places and times. Generating our way to a form of mass, weaponised laziness cannot equate to productivity and quality gains we normally prioritise. How is the ability to generate images already reviled as ‘AI slop’, an improvement on the limitless quantities of existing stock imagery? As usual, the people promising ‘revolution' have a subscription service to sell you, nothing more.

The machine that’s us

This central tension reflects contradictory inclinations we have as humans: we prize authenticity, but we would love the power to tweak reality. We value skills and effort, but are eager to take shortcuts to get things done.

If the venture capital loves a boom element seems predictable, in other ways generative AI’s shortcomings have also reminded us what an odd thing it is to be a human. We aren’t just language utterers. We’re conscious and intelligent, yet struggle even to define what we mean by those terms. Just as a dictionary and dice do not make a brain (or intelligence), what we want from artists, writers, musicians, film makers… isn’t usually predictable, even if Hollywood studios would love an app to spit out another 34 Marvel films.

We encounter art and creativity to be flummoxed, charmed, wrong-footed, and inspired. So much of why we value this work lies not in knowing or predictability, but the opposite. We look to art to discover new worlds, experience overwhelming emotions, surprise, mutual discovery, to gain a sense of presence with the ineffable. We will never truly know what it’s like to be someone else. Art is just one of the few ways we attempt to overcome this fact. We should stand up for our inability to know what’s going on. Our mystery is our energy, it makes life interesting.

Generative AI tools’ mirror-like, open-ended nature is intoxicating, just as their usually cheery tone charms us, especially when delivered with a seductive Hollywood A-lister’s voice. The question of how our talents, shortcomings, personal development and authenticity still fit in a world where we’ve used technology to atomise and summarise all human endeavour in this way, remains hard to grasp. (I shall forgive you dear reader, if you used AI 15 minutes ago, to summarise this article for the sake of time.)

Generative AI may not have yet totally rocked your world, or rewritten your job description. But its tanks are planted on our lawns. And in its ability to compress much of our culture and history into an invisible box whose ultimate purpose is unclear, in its destabilising implications for so many things we hold dear, generative AI is perhaps the most human thing we have ever made.

What have we learned (if anything)?

— Human intelligence isn’t just abstract thinking, it’s embodied and social

— We value creativity precisely because it is mysterious

— Songs are written by people, and made out of lives led on Earth

— Generated is an uglier word than ‘created’, ‘painted’, ‘composed’ etc.

— Your brain is not a computer; an artist is not AI

— Venture capital would have you believe anything

— For humans, the work is as valuable as the outcome

— Digital innovations are presented as inevitable, but aren’t (just ask the metaverse)

— In reality, isn’t this who we are? (so charming!)

Alexander Mayor

This article is an EM GUIDE special curated by the editors of the EM GUIDE members and created in response to current trends and issues of the regional and global music industry.

Pictures are generated by Alexander Mayor using Midjourney.